Why and How the CPC Works in China

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China.org.cn, June 30, 2011

E-mail

China.org.cn, June 30, 2011

Fanshen

China's land issue was an old problem. "Land to the tiller" had been the cry for over 2,000 years, in peasant revolt after peasant revolt. However, mere changes of dynasty had failed to change the fate of the peasants. It was left to the CPC to solve this age-old problem.

In old China, before 1949, the land tenure situation of various classes was extremely irrational. Jack Belden, an American, pointed out in his book China Shakes the World that in general, landlords and rich peasants, who accounted for about 10 percent of the population, owned 55 to 65 percent of the land. A more accurate estimate would be 70 to 80 percent. To change this situation, on May 4, 1946 the CPC issued the "Instructions on Land Issues," which announced the CPC's support for the masses in their efforts to acquire land from the landlords, in struggles against traitors, exposing and criticizing their crimes, and in struggles for reduction of rent for land and of interest on loans.

As the US journalist Anna Louise Strong related in her book The Chinese Conquer China, in the CPC-led land reform from 1946 to 1947 the party did not simply confiscate land – it was assigned to farmers through redemption, donation, punishment, social pressure, confiscation and other approaches supported by various sectors of the community. Not until September 1947, when the CPC promulgated "The Outline of the Land Law of China," was the "land to the tiller" policy in which the land was equally distributed really implemented. By the first half of 1949 in the old liberated areas like Northeast China, North China, Northwest China and East China's Shandong and Northern Jiangsu provinces, and the newly liberated small areas surrounded by them the land had basically been distributed evenly, and nearly 100 million peasants had acquired land for the first time.

The CPC-led land reform not only enabled the peasants to get the land they were eager for, but also helped them partake in politics, in which they had long been marginalized. On June 12, 1944, Mao Zedong pointed out to the Chinese and foreign press corps that the problems of China were due to lack of democracy, and the CPC demanded that the national government, the KMT and all the political parties implement democracy. Democracy had to be all-rounded, and it had to be implemented in political, military, economic, cultural and party affairs, and international relations.

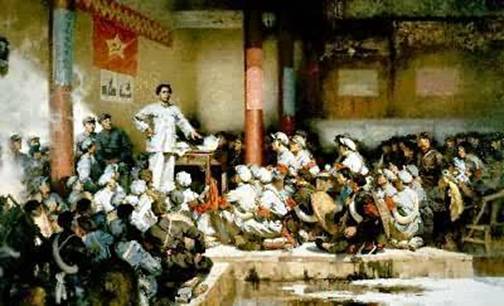

Since the beginning of the Anti-Japanese War, the CPC had established a "triangular organization" system, in which the CPC, the non-party leftists, and the middle party held one third of the power each, in its border regions, and formulated the "Election Ordinance of the Shaanxi-Gansu-Ningxia Border Region." To ensure that elections could be carried out normally and according to law, considering that most peasant voters were poorly educated and many people could not read, the border region government created a variety of ways to enable people to vote, including drawing circles and moving beans from one pot to another. Voters displayed considerable enthusiasm, and the turnout rate of the border region elections could always be maintained above 80 percent.

Peasants had always been considered the most poorly organized group in China. But the CPC knew well that once someone could put forward correct proposals representing their interests and organize them effectively, their full potential would be realized and they would become a surprisingly strong driving force. Therefore, the CPC's successful policy toward the peasants won the wholehearted support of the majority of them. They flocked to join the army and supported the front. In the province of Shandong alone, during the Chinese Civil War (1946-1949) 950,000 men joined the Communist forces, and more than 11.06 million rural laborers and militiamen were mobilized to help the army to transport materials.

Moreover, the CPC-led rural reform completely changed the appearance of China's rural areas and the attitudes of the peasants. William Hinton, an American who was teaching at the North China University in the Shanxi-Hebei-Shandong-Henan liberated area, said after observing the post-land-reform rural society: "The Chinese revolution created a whole new vocabulary. A most important word in this vocabulary was fanshen. Literally, it means 'to turn the body,' or 'to turn over.' To China's hundreds of millions of landless and land-poor peasants it meant to stand up, to throw off the landlord yoke, to gain land, stock, implements, and houses. But it meant much more than this. It meant to throw off superstition and study science to abolish 'word blindness' and learn to read, to cease considering women as chattels and establish equality between the sexes, to do away with appointed village magistrates and replace them with elected councils. It meant to enter a new world…"

John Leighton Stuart, who was familiar with the situation in China, said, "Virtually everyone agrees that the Communist issue in China will never be settled by military means. The natural corollary to this is that it can only be settled by giving the rural masses a better local government than that of the Communists. The nature of this is fully expounded in the 'Third Principle' of Sun Yat-sen, the Lincolnian 'Government for the People,' but its neglect was one of the greatest weaknesses of Kuomintang rule."

Although the KMT also had a theory about land issues, it did not come up with an effective way out, and was overtaken by failure on the mainland. The KMT did not reform the land system, but collected more and more taxes from the peasants. During the civil war, the government's demand for grain and other agricultural produce was four or five times as much as in 1936, and in some places it was even more than 20 times. The CPC, on the contrary, abolished sundry taxes and levied main taxes only. As a result, the lives of peasants in the KMT-controlled areas and in the Communist-liberated areas were virtually a tale of two worlds.

Lloyd E. Eastman, an American scholar, said: "Finally, the Nationalist failure in the countryside – the regime's inability to assure land, security, and food to the peasants—sharply diminished the respect the peasants held for the government. The government, that is, was losing legitimacy. The heavy and frequently inequitable exactions, the corruption, and the bias that most officials showed for the landlord class against the tenants, all undercut the authority of the government and the social value traditionally attached to licit behavior. As a result, peasants evaded the tax collectors and fled the conscription officers… The result was, in effect, to create a pressure differential: little pressure (or support) on the Nationalist side; some pressure (support) on the Communist side. A partial political vacuum favoring the Communists was thereby created."