Peking opera and its Chinese keywords

- By Zhou Jing

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, October 10, 2023

E-mail China.org.cn, October 10, 2023

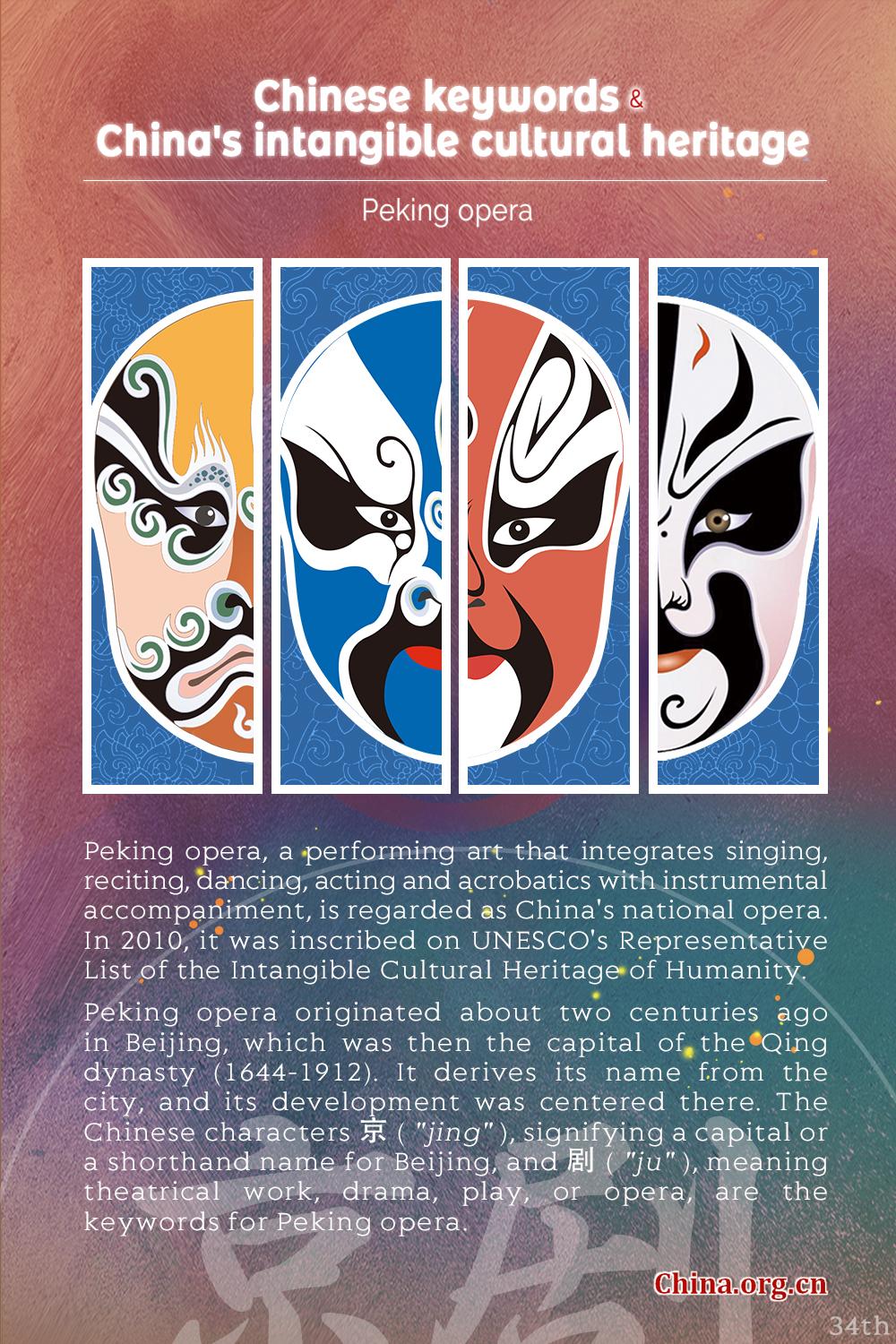

Editor's note: Peking opera, a performing art that integrates singing, reciting, dancing, acting and acrobatics with instrumental accompaniment, is regarded as China's national opera. In 2010, it was inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Peking opera originated about two centuries ago in Beijing, which was then the capital of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). It derives its name from the city, and its development was centered there. The Chinese characters 京 ("jing"), signifying a capital or a shorthand name for Beijing, and 劇 ("ju"), meaning theatrical work, drama, play, or opera, are the keywords for Peking opera.

Peking opera is believed to have developed from several ancient local operas. In 1790, a local opera troupe named Sanqing, backed by a prosperous businessman, traveled from Anhui in east China to Beijing to perform for Emperor Qianlong's 80th birthday celebrations. The performance was a great success, drawing more Anhui opera troupes to come and perform in the city. By blending the different performing techniques of these troupes and adopting artistic styles from Han opera, Kunqu opera, and Shaanxi opera, Peking opera gradually developed its unique style.

Although Peking opera is widely practiced throughout China, its main performance centers are in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai. The opera is sung and recited primarily in Beijing dialect, and its librettos are composed following a strict set of rules that emphasize form and rhyme.

Performers use the medium to narrate stories about history, politics, society, and daily life, aiming to inform or entertain audiences. According to UNESCO, the music of Peking opera plays a vital role in determining the show's pace, establishing the atmosphere, defining characters, and guiding the progression of the stories.

All roles in Peking opera are defined according to gender, age, personality, profession, and social status. Today, audiences are familiar with four types of roles, including sheng (male role), dan (female role), jing (painted face male role), and chou (clown). The well-known Peking opera master Mei Lanfang (1894-1961) was celebrated for his performances in the dan role and founded the Mei school. During the 1920s and 1930s, he was invited to perform Peking opera in Japan, the United States, and the Soviet Union, significantly enhancing cultural exchanges between these nations.

Peking opera has many prominent schools, including the renowned Tan School, Mei School and Cheng School. These schools were named after their master performers — Tan Xinpei, Mei Lanfang, and Cheng Yanqiu, respectively — as the artistic success of Peking opera is often gauged by the achievements of its leading performers.

Different schools concentrate on various types of roles and have their own signature artists. For example, the Tan School is known for specializing in the role of the older man (lao sheng), while the Mei and Cheng schools are focused on the woman's role (dan).

Based on these role types, facial makeup and costumes are designed specifically for each type of role. Audiences can discern the personality of a role through the colors and painting patterns of an actor's facial makeup. For example, a red-faced character signifies valiance, loyalty, and positivity, while yellow-faced and white-faced characters are viewed as sinister, treacherous, and hostile. Additionally, a distorted face, drawn with asymmetrical lines, generally represents a vicious villain or accomplice.

Costume designs reflect the social rank of the role. For instance, royal families wear yellow robes, and high-ranking officials wear purple or red dresses, all with rich embroidery, while lower-ranking officials normally wear blue and simple-patterned clothes.

During the over-200-year development of Peking opera, more than 1,000 plays were created, many of which have become classics beloved by generations. However, in the second half of the 20th century, Peking opera witnessed a steady decline in popularity due to changing musical tastes and lifestyles. In response, Peking opera circles began to reform this classic art in the 1980s, making efforts to increase performance quality and incorporate modern elements to attract more audiences.

Today, several units remain dedicated to the protection and development of Peking opera, such as China's National Center for the Performing Arts, National Peking Opera Company, and Shanghai Jingju Theatre Company, among others. They conducted bold experiments by introducing Western symphony into performances, video recording and broadcasting classic opera productions, pairing the sound records of late artists with the performances of today's outstanding performers, and producing Peking opera films.

"Peking opera is transmitted largely through master-student training, with trainees learning basic skills through oral instruction, observation and imitation. It is regarded as an expression of the aesthetic ideal of opera in traditional Chinese society and remains a widely recognized element of the country's cultural heritage," UNESCO described.

Find out more about China's intangible cultural heritage and their keywords:

China's 43rd UNESCO's ICH element: Traditional tea processing

China's 42nd UNESCO's ICH element: Wangchuan ceremony

China's 41st UNESCO's ICH element: Taijiquan

China's 40th UNESCO's ICH element: Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa

China's 39th UNESCO's ICH element: Twenty-Four Solar Terms

China's 38th UNESCO's ICH element: Abacus-based Zhusuan

China's 37th UNESCO's ICH element: Training plan for Fujian puppetry performers