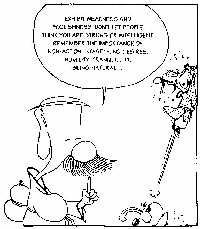

Born in 1948, Cai Zhizhong, a popular Taiwain cartoonist, was

the first to use cartoons to illustrate the seemingly recondite

ancient Chinese classics in such an amusing way. China has a wealth

of spiritual heritage, including philosophical thoughts, poems from

the Tang dynasty (618-907), the Book of Changes and

Zen Buhhdism. According to Cai, this wealth of spiritual

heritage may not be easily understood, prompting his attempts to

express these complex ideas with simple and interesting

cartoons.?

Starting from the 1980s, Cai created a series of Chinese comic

books on ancient Chinese classics, like Zhuangzi Speaks: The

Music of Nature, Zen Speaks: Shouts of Nothingness,

Confucius Speaks: Words to Live By, Sunzi Speaks: The

Art of War, and The Tao Speaks: Lao Tzu's Whispers of

Wisdom. Confucius, Lao Tzu, Zhuangzi, and Sunzi are widely

credited as sages whose thoughts have played an important role in

China's development.

Cai put his unique understanding and feelings of ancient

thoughts into his cartoons, and added a modern interpretation of

them, making boring ancient philosophies quite amusing as well as

understandable. His works won a large number of adult readers for

comic books, a market predominantly children-targeted. This series

of comic books has hoarded great applause from readers both in

Taiwan and mainland China, with 4 million copies sold in

Taiwan.

Among all of his works, Zhuangzi Speaks: The Music of

Nature, published in the 1986, was the most successful.

Remaining on the top of the bestselling literature in Taiwan for

ten months, this book had quite an influence of the mainland boom

of Taiwanese literature in the late 1980s.

Cai Zhizhong's cartoons about the sayings of Confucius, Laozi,

Sunzi, Zhuangzi, and Mencius were later made into three-dimensional

cartoons.

A borderless language

Cai's works have provided him much popularity, and have been

translated into dozens of languages. Currently, readers in 40

different countries have access to Cai's works and up to 40 million

copies have been sold. More than 15 printing machines are said to

print his works each day.

Cai's latest work is the cartoon-illustrated Traditional Chinese

Culture Series. Published by Beijing-based Modern Press in June

2005, this version differs from the previous version in that the

text was written in English while the original ancient Chinese

characters were kept in the margin. Ten titles about the theories

of Tao, Confucius, and Zen Buddhism are included in this series.

The translation was done by Brian Bruya, a Ph. D. in philosophy at

Hawaii University. According to Cai, Brian's translation made his

works more understandable, further promoting his works by making

them more readable.

100 thousand copies were printed in the initial release, among

which 10 thousand were made public to readers in Taiwan, Hong Kong,

Macao, Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, North America and

Europe.

Cai hopes foreign visitors will purchase parts of his comic series

on traditional Chinese culture as souvenirs while in China. Some

worry that foreigners may not appreciate the Chinese sense of humor

in his book, but Cai thinks that cartoons are an international

language like music and dance, bearing no borders.

In addition to traditional Chinese classics, Cai published comic

books on Calculus, Algebra, and Physics in 2005. Cai was extremely

proud of himself, believing that his works would be able to arouse

students' interest in learning by making these subjects more

enjoyable.

A degage cartoonist

Cai lives a rather laid-back lifestyle, indulging himself in

whatever he likes and always feeling happy and free. He has always

emphasized doing things that he loves like cartoons and the fine

arts. He feels that the best choice in his life was selecting

"interest" as a lifelong career. He draws cartoons simply for the

intrinsic rewards it provides him, not for money or a good

reputation. He relates his job to his basic needs, and feels that

drawing cartoons is just like drinking coffee or tea when he's

thirsty.

Cai began to draw cartoons as early as middle school, and

various presses often accepted his works. At 15, he was invited by

a press in Taipei to work as a professional cartoonist. It had been

his dream for years. Cai decided to quit school for work, and when

he discussed this plan with his father, his father simply agreed

with silence. This was rather rare among Chinese parents, who are

famous for their paternalistic manner in deciding the future for

their children.

|

Cai has a wide range of interests, from drawing cartoons to

collecting figures of Buddha, as well as playing bridge, gardening

and interior decoration. Having so many hobbies never had any

negative affects his career as a cartoonist. On the contrary, his

various other hobbies often provide inspiration. For instance, his

collection of Buddha figurines provides additional insight for his

Zen cartoons, and playing bridge is a great way to relieve the

stress associated with a lot of difficult work.

Differing from most Chinese parents, Cai has a unique way of

bringing up his daughter, stressing independence and self-reliance.

His daughter even traveled to Japan by herself at the age of 12..

With the influence of her father, his daughter has also become fond

of cartoons. Her creativity and originality is comparable to that

of her father, and many of her cartoons have been published as

well. Cai once made a comparison between human beings and wolves,

stating that a parent wolf never teaches its children the necessary

skills of survival, leaving the child with the challenge of

acquired these skills on their own.

(ChinaCulture.org June 22, 2006)

|