Going far and wide to predict climate change

Dismayed by ice and storms, British explorer Captain James Cook had no regrets when he abandoned a voyage searching for a fabled southern continent in 1773.

Finding only icebergs after he was the first to cross the Antarctic Circle, he wrote ruefully that if anyone ventured further and found a "land doomed by nature...to lie forever buried under everlasting ice and snow":

"I shall not envy him the honor of discovery, but I will be bold to say that the world will not be benefited by it."

Things may be worse than he thought.

Climate change is turning Antarctica's ice into one of the biggest risks for coming centuries. Even a tiny melt could drive up sea levels, affecting cities from New York to Beijing, or nations from Bangladesh to the Cook Islands - named after the mariner - in the Pacific.

Scientists are now trying to design ever more high tech experiments - with satellite radars, lasers, robot submarines, or even deep drilling through perhaps 3 kilometers of ice - to plug huge gaps in understanding the risks.

"If you're going to have even a few meters it will change the geography of the planet," Rajendra Pachauri, head of the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), said of the more extreme scenarios of fast ocean rise.

Antarctica locks up enough water to raise sea levels by 57 meters (187 ft). Greenland stores the equivalent of 7 meters.

Eventually discovered by Europeans in 1820, Antarctica may have first been reached by the treasure fleet of Chinese admiral Hong Bao in 1422 in his quest to find the navigational equivalent of the North Star in the southern hemisphere. In his ground-breaking book 1421, British author Gavin Menzies notes that climate change was a factor even then: a map he's convinced was created by the Chinese shows Graham Land, the northern extremity of the Antarctic peninsula, largely ice-free, which would have been possible during several short periods of the 15th century.

Worries about sea level rise are among the drivers of 190-nation talks on a new UN deal to combat climate change, mainly by a shift away from fossil fuels, due to be agreed in Copenhagen in December.

Fear of collapse

Scientists are concentrating on the fringes, where the ice meets a warming Southern Ocean. "It's the underside of the ice sheets that's crucial," said David Carlson, a scientist who headed the International Polar Year from 2007-08.

Warmer seas may be thawing ice sheets around the edges, he said, and allow ice to slide off the land into the sea more quickly, adding water to sea levels. But it is hard to be sure because of a lack of long-term observations.

Recent studies indicate a slight warming trend in Antarctica, teased out from computer studies of temperature records. Still, most of Antarctica is not going to thaw - the average year-round temperature is -50 Celsius.

One possibility is to look far back into history.

Studies indicate that in the Eemian about 125,000 years ago, for instance, temperatures were slightly higher than now, hippopotamuses bathed in the Rhine - and seas were 4 meters higher.

"We need to know where the extra four meters came from," said David Vaughan, a glaciologist at the British Antarctic Survey, adding that one possibility was that West Antarctica's ice had collapsed.

|

|

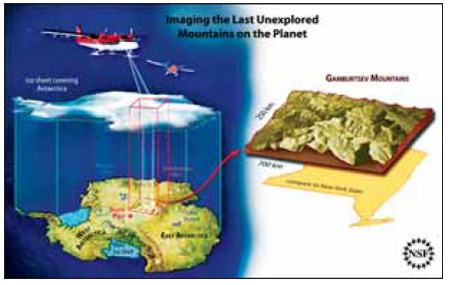

David Vaughan, a leading glaciologist with the British Antarctic Survey, looks out through rain at the Sheldon glacier on the Antarctic Peninsula in this January 2009 file photo. (blow) An artist's rendering of the Antarctica Gamburstev Province project is seen in this handout image from the National Science Foundation. Scientists are trying to design ever more high tech experiments - with satellite radars, lasers, robot submarines, or even deep drilling through perhaps 3 kilometers of ice - to plug huge gaps in understanding the risks. [Reuters] |

He said that an operation to drill through ice - about 3 km thick - to bedrock could help find out. West Antarctica is vulnerable because its ice rests on rocks below sea level and holds enough ice to raise sea levels by 3-6 meters.

A sample of rocks beneath the ice would reveal if and when they had last been exposed to cosmic rays - which cause chemical changes that can be read like a clock. There could also be fossils or ancient sediments under the ice to fix dates.

If the ice had collapsed in the Eemian or during other warm periods between Ice Ages, it would set off global alarm bells about risks of a fast rise in sea levels, Vaughan said. A finding that the ice had been stable would be a huge relief.

0

0