Bangkok and the perils of overdevelopment

- By Geoffrey Murray

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China.org.cn, November 3, 2011

E-mail

China.org.cn, November 3, 2011

|

|

|

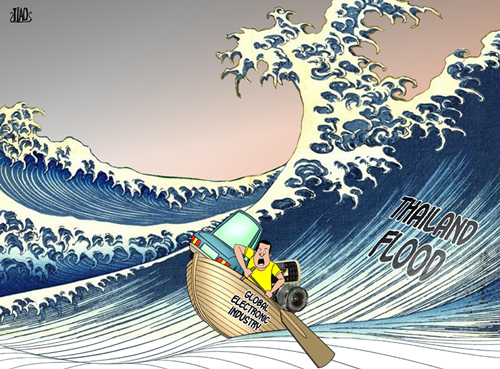

Collateral damage [By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

Flooding is nothing new there. I recall dining with Thai friends once and being unable to get back to my hotel, eventually spending the night at their villa in a drier outer suburb.

Yet the severity of the current disaster is a worry with major damage to the city's infrastructure and its international image.

The necessity to open overflowing dams up-country transferred the problem downstream to the Chao Phraya River flowing through the capital. Efforts to channel this into the Gulf of Thailand were then frustrated by high seasonal tides.

From research carried out over several visits to Bangkok, I don't think there's much doubt the problem lies with the city's poor location and frenetic development. With a population of 10-12 million and traversed by more than 1,000 canals, it is only 1 to 1.5m above sea level and is built on soft, loamy soil.

This has been undermined by the sinking of innumerable water wells to meet the city's various needs over many decades; the aquifers (underground water-containing layers of permeable rock, clay, sand, etc) have been pumped dry leading to ground subsidence.

With ambitions to be seen as an international business and financial center, Bangkok has been throwing up numerous tall - and heavy - high-rise office and apartment buildings. The weight of all that steel and concrete is not really supportable and so the city steadily sinks into the ground by an estimated average of more than three inches a year.

On one research tour, I was shown around the city by a Canadian expert who was developing a project to stop or even reverse the sinking and shown places where the road had become elevated as the buildings lining it had sunk; huge cracks in the sides of buildings showed the great strains being imposed.