Eurozone needs reform to keep dominos standing

- By Ni Xiaolin

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, December 12, 2011

E-mail China.org.cn, December 12, 2011

The European dominos are beginning to wobble. Whether or not they are impervious to the debt crisis in Greece and other parts of the eurozone remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: Those who hope for a speedy economic recovery in Europe will be disappointed.

|

|

|

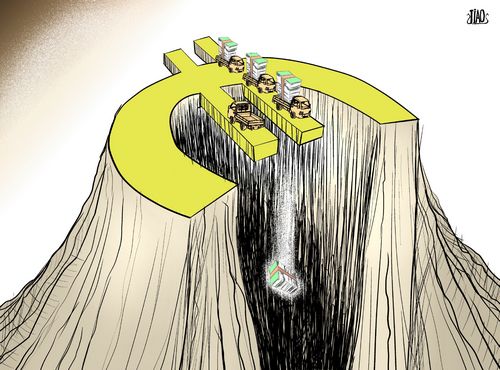

Into the abyss [By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

Economists both at home and abroad are not optimistic about the crisis. Many rating agencies have continually lowered their outlooks on the growth of global economy for next year. It seems the European debt crisis has not knocked down its last domino.

The U.S. financial crisis that broke out in 2008 is clearly linked with the present crisis. Both were products of economic imbalances. Notably, the European debt crisis has entered a new phase in the second half of this year, with frequent leadership changes in many European countries making the direction of policymaking increasingly unpredictable. Widespread hopes that new leadership will solve the crisis may be misplaced.

The debt crisis stems from systematic barriers embedded in the eurozone since its establishment. Those who spend the money serve different masters from those who manage it. Politicians in some countries issued much more sovereign debt than their economies could afford. And now that it has come time to pay off the national credit cards, they are refusing to take responsibility for their fiscal temerity. As such, a number of policymakers have suggested integrating the eurozone's fiscal policy, concentrating the responsibility for both managing and spending money under one roof.

Obviously, the stronger economies in the region would not agree to such a proposal. With their higher labor productivity and quicker economic growth, these countries are afraid their financial reputation would be dragged down by reckless over-spenders.

Not long ago, French President Nicolas Sarkozy publicly advocated a "two-speed Europe" theory with more integration in the eurozone and less elsewhere in the European Union. In my opinion, a remedy like fiscal integration cannot be realized until all the countries in the eurozone have been engulfed by the debt crisis.

The solution for the crisis now is not bailout but rather reform. Some observers once criticized former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berluscconi for using the number of customers in restaurants as an indicator of domestic economic development. Berluscconi thought full restaurants meant a prosperous economy.

What Il Cavaliere failed to notice, some analysts argued, was the "hollowing out" of Southern European countries such as Italy, where the comforts of a welfare state have bred laziness. Indeed, the current rising unemployment rate and steady decline of incomes in Southern Europe is a product of both the continent's economic turbulence and poor policy choices.

The author was former deputy director of Xinhua Beijing branch, senior correspondent of Xinhua and engaged in financial reporting.

(This post was translated by Li Shen.)

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)

Add your comments...

Add your comments...

- User Name Required

- Your Comment

- Racist, abusive and off-topic comments may be removed by the moderator.