Chinese government strongly supports high-level expert advice

- By Richard de Grijs

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, March 22, 2017

E-mail China.org.cn, March 22, 2017

|

|

|

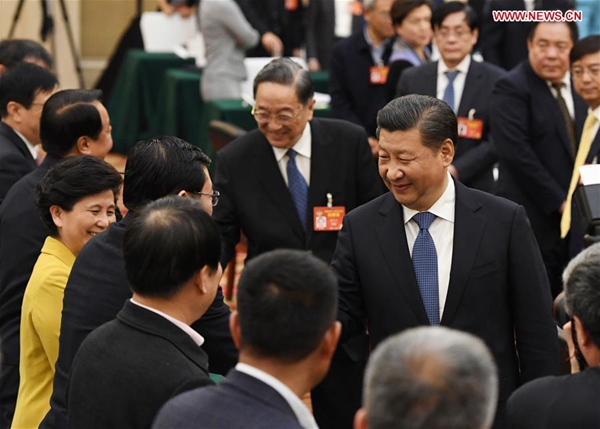

Chinese President Xi Jinping joins a panel discussion with political advisors from the China Association for Promoting Democracy, the Chinese Peasants and Workers Democratic Party and the Jiu San Society at the fifth session of the 12th National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) in Beijing, capital of China, March 4, 2017. Yu Zhengsheng, chairman of the National Committee of the CPPCC, also joined the panel discussion. (Xinhua/Rao Aimin) |

On March 4, President Xi Jinping participated in a panel discussion with advisors from across the Chinese political spectrum to examine the country's future development needs. He came out in strong support of the nation's experts, stating that China urgently needs its intellectuals to facilitate further enhancements to national prosperity, rejuvenation, and wellbeing.

In fact, he said that the Chinese top leadership has always considered the country's high-level experts as "the elites of society, pillars of the nation, pride of the people, and treasure of the country." This faith of the central government in its senior scientists and engineers appears unshakeable.

President Xi also emphasized his view that the nation's experts should adopt a sense of urgency and responsibility to work towards making China a major scientific and technological power. I found it particularly encouraging that he also said that authorities should trust the country's technical experts and seek their advice when reaching policy decisions.

Now contrast these developments with those that led to the U.K.'s unexpected Brexit vote. In the run-up to the British June 23, 2016 referendum, opponents to the U.K. government's arguments to "remain" part of the European Union were particularly vocal in their denouncements of expert opinions.

Similarly, both during the recent U.S. election campaign and now under the new Trump administration, expert advice was and is routinely ignored, demonized, and replaced by "alternate facts." When politicians place short-term business interests before their nation's urgent needs to cope with long-term threats such as those associated with man-made causes of climate change, expert advice is apparently no longer needed.

Scientific truths include, by definition, a degree of uncertainty: Scientific claims only make sense if you know the constraints under which they apply! Yet, in 2006, the former Canadian prime minister introduced new guidelines that prohibited federally employed scientists from talking freely about their research with the press, risking their jobs if they flouted the ban. A leaked memo revealed an 80 percent decrease in engagement with the press as a result. The ban was only reversed in 2015.

One of U.S. President Trump's first executive orders banned federal employees in many scientific agencies from any external communication. His administration reportedly imposed that "[Environmental Protection Agency] scientific studies, data undergo review by political staff before public release." In addition, the Trump administration appointed a new director to the agency who has publicly expressed doubts as to the reality of man-made causes of global warming.

In China's big cities we encounter the effects of man-made excess particulate matter on a regular basis. Deliberations during the recent political season have sent a strong message to polluters that the authorities will be on their backs if they don't reduce their environmental footprint.

The supportive attitude of the Chinese government to its high-level experts likely reflects the differences in make-up of the Chinese government on the one hand and those in countries like the U.S. or the U.K. on the other. A significant fraction of Chinese government officials have technical, scientific, or engineering backgrounds; few, if any, of their U.S. and U.K. counterparts can boast the same.

Nevertheless, in an increasingly globalized world and given China's sustained rise as one of the world's most important geopolitical players, it is crucial to secure the continuing support and interest in science of the population. In turn, this calls for more dialogue between the nation's scientists and the general public.

In June 2010, the Chinese Association for Science and Technology announced ambitious plans to double the country's science communicators by 2020. "The four million number," said Yin Hao, vice minister of the association's popularization department, "will include 500,000 full-time and 3,500,000 part-time communicators, including 2.2 million volunteers," who would be based predominantly in less developed rural areas.

While China's science museums and planetaria are enjoying record visitor numbers, efforts to involve the country's practicing scientists have so far not materialized to any significant extent. I think that this is a missed chance in the context of the country's rapid development.

In many Western countries, a public engagement component is integral to any successful research project. In some countries, including the U.K. and Australia, the relatively poorly defined concept of "impact" of one's research is now one of the aspects on which scientists' success is rated.

While this may be a bridge too far in the Chinese research environment, sustained encouragement of scientists to engage with members of the general public would certainly enrich discussions and the appreciation of scientific advances in society at large.

Richard de Grijs is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://m.formacion-profesional-a-distancia.com/opinion/RicharddeGrijs.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.