Going for depth in life’s experiences

- By Eugene Clark

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, September 16, 2017

E-mail China.org.cn, September 16, 2017

|

|

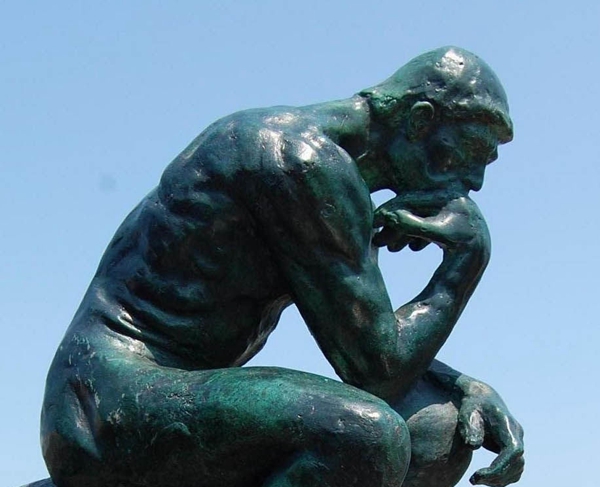

The Thinker, a bronze sculpture by Auguste Rodin [File photo] |

In learning, in thinking, in work as well as in life, it is important to go deep rather than wallow idly in the shallows of experience.

In education theory and practice, the best teachers focus on “deep learning.” In reading for comprehension, for example, they teach students to search for meaning, to pay attention to context, to relate what they read to other things that they have read, what they already know and have experienced.

Deep readers will read a work several times, with deeper understanding each time. Shallow readers, in contrast, focus on the surface of an article and seek to make guesses as to meaning without ever really understand what they are reading.

In regard to deep versus shallow listening, William Hazlitt once wrote, “The art of conversation is the art of hearing as well as of being heard.” Deeper listeners seek to grasp the underlying ideas and principles that will enable them to make sense of the facts and even to anticipate and apply these principles to new sets of facts.

I remember my early days of university debating. In a panic, I would try to write down everything the opposing speaker had said. Later, I learned to just listen deeply for a moment and understand the basic idea/argument that I could then fit together in an integrated whole and then produce a deeper rebuttal of the opposing case.

This principle of deep versus shallow also applies to the world of work. Cal Newport’s recent book Deep Work tackles this issue. Deep work, he argues, is high-value work that is uncommon and hard to replicate by artificial intelligence or even by outsourcing.

In contrast, shallow work is at the low end of the value chain, easily replicated and far more common and more likely to be outsourced or taken over by a machine. Deep work requires focused attention and reflection.

Obviously, shallow thinking is superficial and only scratches the surface. It sees the obvious, but misses the subtle. Deep thinking understands the relationships of things. It digs deeps, notes exceptions and is able to distinguish things that on the surface seem simple and indistinguishable.

Going deep also relates to the mastery of a skill. In contrast to Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers in which he contended that masters in a given area put in about 10,000 or more hours to master their skill, more recent work instead stresses the quality of practice. Thus, at a deeper level, it is not only the hours that you practice, but the deliberate nature of that practice.

This includes thinking deeply about what you are doing, ensuring you have feedback loops so that you are committed to going beyond your present state of competence and pushing deeper.

We live in a world that is getting more and more crowded with our own realities and interests colliding, thus leading to conflict and frustration. The management literature distinguishes between deep and shallow coping. Shallow coping strategies are characterized by such aspects as doing nothing, people-shuffling, delaying and similar other tactics. Deep coping, however, is characterized by adaptation, flexibility, consensus building, creativity, thinking outside the box and so on.

Leaders, especially those engaged in significant change management, must be resilient. They have deep coping skills.

It is our consciousness which makes us human. That consciousness is at its best when we are deep in thought, focused, and critically and imaginatively engaged. Unfortunately, in our 24-7 existence, in which ever new and invasive technologies vie for and increasingly dominate our attention, it is becoming difficult to achieve such deep focus.

In this age of constant disruption, individuals and organizations need to design workplaces, homes and other spaces so we can better focus and be attentive and conscious of and reflective about what we are doing and why. In the words of poet, Mary Oliver, “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work.”

Finally, the deep versus shallow metaphor extends to life experiences and character building in general. As humans, we should strive to develop our talents to the full, to develop a deep understanding of ourselves, our world and our place in the world. As Martin Luther King stated so eloquently, we need to judge our fellow human beings not by the “color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

Eugene Clark is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://m.formacion-profesional-a-distancia.com/opinion/eugeneclark.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors only, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.