?Emigrant return policies may slow 'brain gain' in China

- By Richard de Grijs

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, December 14, 2017

E-mail China.org.cn, December 14, 2017

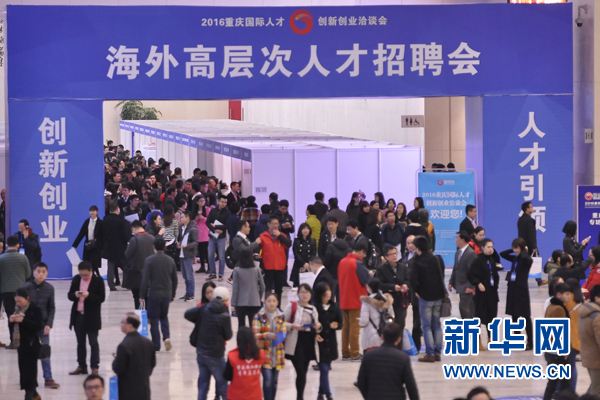

A job fair for foreign-educated graduates held in Chongqing in 2016. [Photo/Xinhua]

In late October, my alma mater in the Netherlands, the University of Groningen, issued a press release announcing the completion of a doctoral dissertation which focused on the benefits of exporting highly skilled labor for the country of origin.

The study's author, Marianna Papakonstantinou, concluded that in countries with high levels of emigration of skilled labor, knowledge-intensive industries experience rapid growth. International migration of highly and moderately highly educated graduates appears to have positive effects on economic development and even stimulate the formation of human capital at home, she found.

Somewhat surprisingly, this implies that an export of skills may result in a "brain gain" rather than a brain drain, in spite of the transfer of human capital away from the country of origin.

The reasons for this seem obvious in retrospect. A significant fraction of migrants may return to their homeland with updated knowledge, experience and high-level skills gained in their host country.

In addition, some of their remittances home are likely used to fund further education by family members. Finally, migrants are often role models for those staying behind, who may, in turn, be inspired to pursue their own higher education potential.

These findings clearly have significance in the Chinese context.

Over the past few decades, large numbers of Chinese students have gained valuable international experience in the highly successful exchange programs supported by the China Scholarship Council, or CSC.

CSC grants allow talented young graduate students to embark on doctoral degrees at prestigious foreign universities. Because they bring their own funding, Chinese students with CSC scholarships are considered attractive targets for active recruitment by overseas graduate programs.

The best of these CSC-sponsored students may be awarded additional support for short-term postdoctoral research abroad immediately following the completion of their doctoral degrees.

However, even the most talented and highly skilled young graduates are obliged to return home for a minimum of two years. If they don't, their guarantors -- often their parents or other close relatives -- may be forced to repay some or all funding awarded to the student as part of their scholarship.

This is where the system breaks down for the most talented Chinese graduates. Such students prefer more flexibility in their professional pursuits. As a consequence, they find CSC scholarships insufficiently attractive, which unfortunately leads the country to miss out on the talents of its best and brightest.

These tough choices are faced by graduates at Peking University every year. Many of the top students agonize about their future choices, feeling overly restricted by the CSC's two-year return policy.

During my time at the university, I have regularly raised these issues in face-to-face discussions with senior CSC officials. Their boilerplate response to these concerns is that CSC scholarships are funded by the taxpayer, so the country has the right to insist that awardees return the favor. While I certainly have no objections to this obligation, the restrictiveness of current policies may in fact be counterproductive to this goal.

Given China's rise in the international pecking order and its robust economy, it is very likely that a large fraction of graduates who migrated abroad on the back of a CSC scholarship will eventually want to return to their home country. I have witnessed this in my own professional field; many Chinese scientists living overseas expressly indicate their keen desire to eventually take up higher-level positions back home.

With more years of international experience under their belts, their native country will most likely gain enhanced benefits from their prolonged stint overseas than if they had returned immediately upon graduation.

And even those graduates who decide to stay abroad will serve as informal ambassadors for their nation and extol the virtues of its education system. This is a scenario that I can directly relate to myself; I left the Netherlands twenty years ago, but I am happy to contribute to efforts by my embassy and the Dutch government's international education support office to promote opportunities back home -- indeed, particularly those supported by CSC scholarships.

For most expatriates, long-term emigration does not mean "out of sight, out of heart." Given the steady improvement of its higher education institutions and the prevailing pressures of the job market, China has reached a stage in its development where the imminent return of its foreign-educated graduates is no longer a necessity. The time has come for the country to consider a significant overhaul of its international student support framework -- for its own sake.

Richard de Grijs is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://m.formacion-profesional-a-distancia.com/opinion/RicharddeGrijs.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.