Old friends and new realities

- By Einar Tangen

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, July 23, 2018

E-mail China.org.cn, July 23, 2018

Against the background of an increasing unpredictable U.S. economic, political and military posture, Chinese President Xi Jinping has embarked on a five-nation tour, starting in the United Arab Emirates and ending in Mauritius, with stops in Senegal, Rwanda, South Africa for the BRICS Summit.

Although the scheduled BRICS Summit in South Africa has been planned long in advance and part of a celebration with old friends, Xi's visit has taken on new significance.

Old friends

On the surface, according to China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, "The visits will promote the further deepening of political mutual trust, mutual development assistance, mutual learning on each other's concepts between China and Africa and the building of a closer China-Africa community of common destiny." Xi will reaffirm old partnerships and friendships, as China looks for stable trade and diplomatic relationships with its longstanding African partners, part of the shared vision for a "community of common destiny." This will probably include new initiatives, like a plan to spur a "new industrial revolution among the BRICS countries."

Xi's message will be consistent with longstanding Chinese policies on trade without ideology, but with a renewed sense of urgency, as it seeks to shore up traditional trade areas and old friendships. Economic links between China and Africa have increased dramatically over the past 20 years. Trade has risen more than 40-fold since the mid-1990s, and China is now sub-Saharan Africa's largest trading partner. China became Africa's largest trading partner in 2009, replacing the U.S.

China's interest in Africa is long standing, both because of resources and past political support in institutions like the U.N. But while trade was focused mostly on raw materials in the past, China's current economic development strategy stresses using infrastructure projects, like the Belt and Road Initiative, AIIB, BRICS and the Chinese Exim Bank, to connect economic development zones and markets, where local manufacturing and services can grow; create industries, jobs, disposable income and a sustainable balance of trade.

It is a simple approach, but one which China has used very successfully in its own development.

New realities

Today the world is experiencing new tensions, where developing and emerging countries seem to be drawing closer together as the developed nations pull further away. The larger realities driving these changes are part economic, part timing and part ideological.

Economics

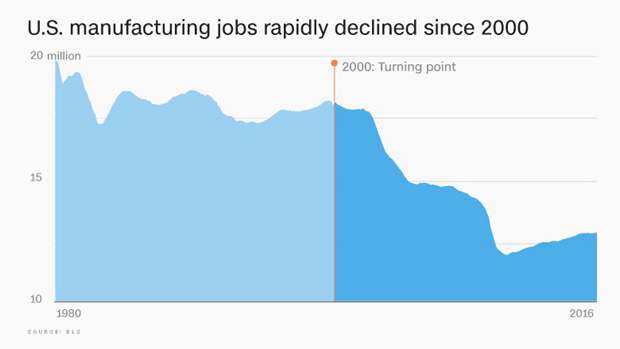

Donald Trump's argument is that U.S. jobs and prosperity were stolen by developing and emerging countries under the WTO. In terms of jobs, he cites the loss of manufacturing jobs in developed countries, like the U.S., with the growth of jobs in developing regions, like Africa, and emerging areas, like Asia.

On the surface the jobs figures back this up, the United Nations reports that the number of manufacturing jobs in industrialized economies declined from 107 million in 1991 to 78 million in 2016; at the same time the number of manufacturing jobs in developing and emerging industrial economies rose from 215 million in 1991 to 279 million in 2016.

In terms of prosperity, Trump points to the lower growth rates over the last 18 years of the developed countries vs. the emerging and developing nations. As can be seen in the World Bank Data Charts below, the U.S. and EU's growth rate lagged behind the world as a whole between 2000 and 2017. As also can be seen during this period, Africa outpaced the U.S. by a margin of almost 5 to 1.

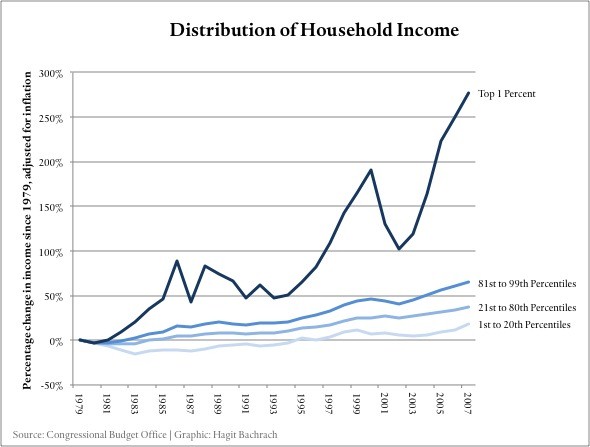

What is not shown in these charts is that while the number of jobs for ordinary Americans decreased and real income stagnated, corporations and elites became vastly richer.

A siren song of lower labor, land, construction and operational costs, offered by countries outside the U.S., has resulted in the relocation of mostly low paid labor-intensive industries and jobs overseas. The reality: Profits made U.S. companies that moved their businesses overseas rich, resulting in a wealthier 1 percent, while American jobs and real earnings declined.

Timing

In terms of timing: The arrival of emerging and developing countries, as economic and political powers, has been perceived as threats to the U.S.'s political, economic and military hegemony, and its desire to lead the world towards a universal Liberal Democratic Capitalist order.

The difficultly is that the world is not ideologically homogenized and today the fast-growing markets of emerging and developing nations are an economic necessity for the future growth of developed nations, like the U.S., whose growth has stagnated.

Therefore, despite having 30 percent of the World's wealth and only 4 percent of its population, which in the past allowed nations like the U.S., to dictate economic, political and military terms, the U.S. may find itself in the curious position of having to negotiate, on a more equal footing, with emerging and developing nations, who represent 89 percent of the World's population and its fastest growing economies, as shown below.

Ideology

Trump's ideology is simply "America First." How he pursues it is often harder to follow, but the reaction to it in developing areas like Africa, is clearer, as noted in a report by noted professor for the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA).

Drawing on polling data from the Pew Research Center, Stremlau charted the dramatic decline in African confidence in the U.S. President "doing the right thing," country by country. For Africans, the president's economic nationalism, hostility to multilateralism, rejection of the Paris accords on climate change, and what many Africans see as discomfort with democratic values, make him an unattractive, even hostile, figure.

These notions are not limited to just developing and emerging areas, neighbors, allies and what Trump has termed "strategic competitors" share the opinion that the U.S. has become a playground bully, intent on tearing down the multilateral world and replacing it with an American hegemony.

The developing and emerging nations that benefited from the multilateral trade regimes like the WTO, having seen the glimmer of economic hope, will not willingly standby and revert to a system which treats them as economic vassals. More likely, as this African trip of Xi will demonstrate, they will band together to protect their futures. Colonialism was a tragic reality, not a wistful memory, and those who think that it is time to revert to the "good old days" will not find willing takers.

Einar Tangen is a political and economic affairs commentator, author and columnist.

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.