Human space exploration gains momentum with China advance

- By Richard de Grijs

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, July 1, 2021

E-mail China.org.cn, July 1, 2021

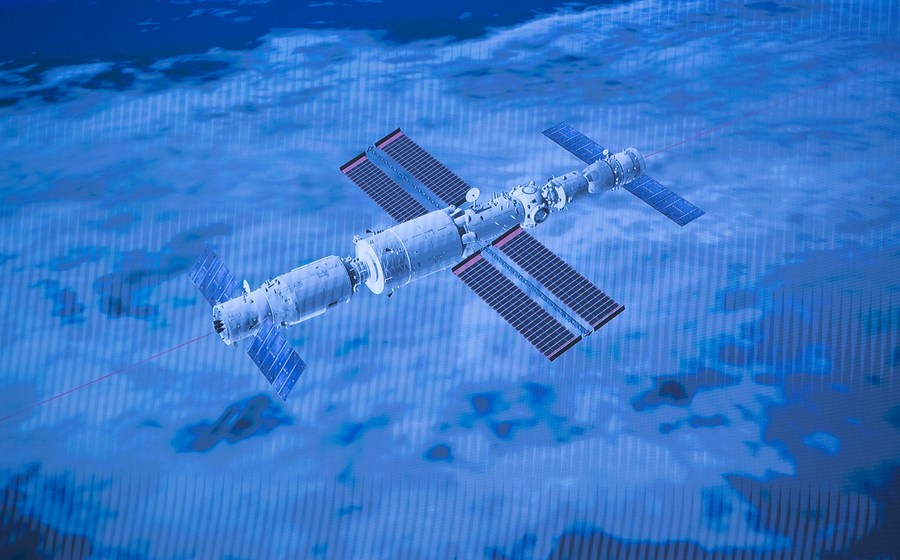

When the three taikonauts on board China's Shenzhou-12 spacecraft docked with the Tianhe space station's core unit on June 17, China joined a select group of nations that have possessed an operational space station.

In fact, the current mission is only the country's first crewed launch since 2016. Nevertheless, China's achievements in both crewed and unmanned space exploration are highly impressive. For instance, in recent years, we have seen a number of soft landings of robotic craft on the Moon, including its far side, as well as on Mars.

Yet, the China National Space Agency's (CNSA) initial pace of development is lagging behind that of the traditionally dominant space nations. It took almost 18 years between China's first orbital flight by Yang Liwei, in October 2003, and the country's first space station. However, China's more deliberate pace reflects the country's carefully planned development of its technology-driven space program.

The current mission is intended to last for three months, with a follow-up mission of six months already planned. In this regard, the Chinese crew, who are highly disciplined, have to deal with the daunting challenge from a psychological perspective, despite much has been learned about long-duration space flight over the past five decades.

The three taikonauts will have their individual, private areas on board Tianhe, but being in a small and confined environment for such a long time could be psychologically challenging.

Another difference between China's current mission and those undertaken by the International Space Station is in management. The Chinese space station is a domestic project, which has raised concerns about whether it will run experiments developed by international teams or host international astronauts in the future.

In this regard, the CNSA representatives have suggested they will expand international cooperation through its space station. As a professional astrophysicist, I'm always excited about the scientific prospects as basic scientific questions benefit from access to extensive brainpower. Hence, I look forward to seeing joint flights of Chinese and international astronauts.

I'll continue to collaborate successfully with my Chinese scientific collaborators, and I indeed relish our productive exchanges and fruitful joint student supervision. I truly hope that the promise and benefits of international collaboration as it pertains to the Chinese space station – in science and in exploring humanity's final frontier – will ultimately benefit us all.

Richard de Grijs is a Dutch professor of astrophysics and Associate Dean at Macquarie University in Sydney.

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.

If you would like to contribute, please contact us at opinion@china.org.cn.