China faces the Eurozone's 'currency war'

- By John Ross

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, March 12, 2015

E-mail China.org.cn, March 12, 2015

|

The headquarters of the European Central Bank (ECB) is pictured in Frankfurt am Main, western Germany, on January 22, 2015. [Xinhua photo] |

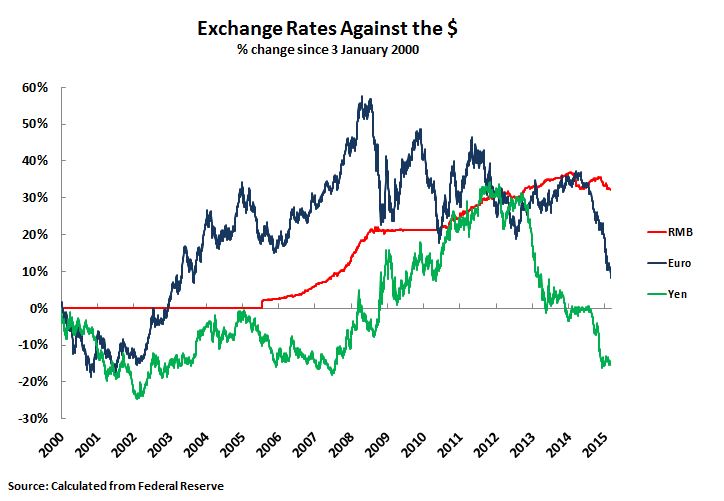

Since mid-2014 the Eurozone has joined what is popularly known as “currency wars" – to use terminology made famous by Brazil's former finance minister Guido Mantega. Between the beginning of June 2014 and the beginning of March 2015 the euro's exchange rate dropped by 18 percent against the dollar. The euro therefore followed the same path of sharp devaluation earlier pioneered among major currencies by Japan's yen – the exchange rate of which fell by 33 percent against the dollar between November 2012 and the beginning of March 2015 under the impact of “Abenomics." The currencies of major developing countries, such as India and Brazil, also sharply declined against the dollar in the last two years.

In assessing the impact on China of this euro currency move, it is not important whether the devaluation was a deliberate policy objective or merely a side effect of the European Central Bank's move towards Quantitative Easing (QE). The effect is the same whether the aim was Euro devaluation or not. Eurozone exporters benefit from this devaluation while exporters to the Eurozone face greater pressure.

The resulting sharp rise in the dollar's exchange rate, against both yen and Euro, had negative effects on U.S. exports by the end of last year. Taking a three month average, to eliminate short term fluctuations, the year on year growth of U.S. goods exports fell from 4.3 percent in May 2014 to 0.7 percent in December. With such low growth rates Obama's goal of doubling U.S. exports is out of reach.

In contrast to major devaluations of the Euro and yen, the decline in the exchange rate of China's currency, the RMB, against the dollar has been small. Since the RMB's all-time high against the dollar, in January 2014, China's exchange rate has fallen by slightly under 4 percent.

These currency trends are shown in Figure 1 – which sets them against the background of longer term exchange rate movements since 2000.

It is important to examine the implications of this sharp Euro devaluation for China. The earlier yen devaluation had a certain limited negative impact on China's exports – the proportion of China's exports going to Japan fell from about 8 percent at the beginning of 2012 to 6 percent by the beginning of 2015. But Japan is a much smaller export market for China than the European Union (EU), of which the Eurozone is the core. The EU and United States are China's largest export markets – each accounting for around 16 percent of China's exports. Europe is similarly important for China's outward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The consequences of euro devaluation are therefore potentially more significant for China than was the yen's earlier decline.

First the trade consequences of the currency movements will be analysed and then the consequences for capital movements – the two sharply differ.

Exports are crucial for China's economy, as China is much more open to trade than either the United States or Japan – the other two of the world's largest economies. This aids China's efficiency, as it makes greater use of international division of labour, but means China's economy is significantly influenced by trends in the global economy. In 2013 China's exports were 26 percent of GDP compared to 16 percent for Japan and 14 percent for the United States.