0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, May 24, 2024

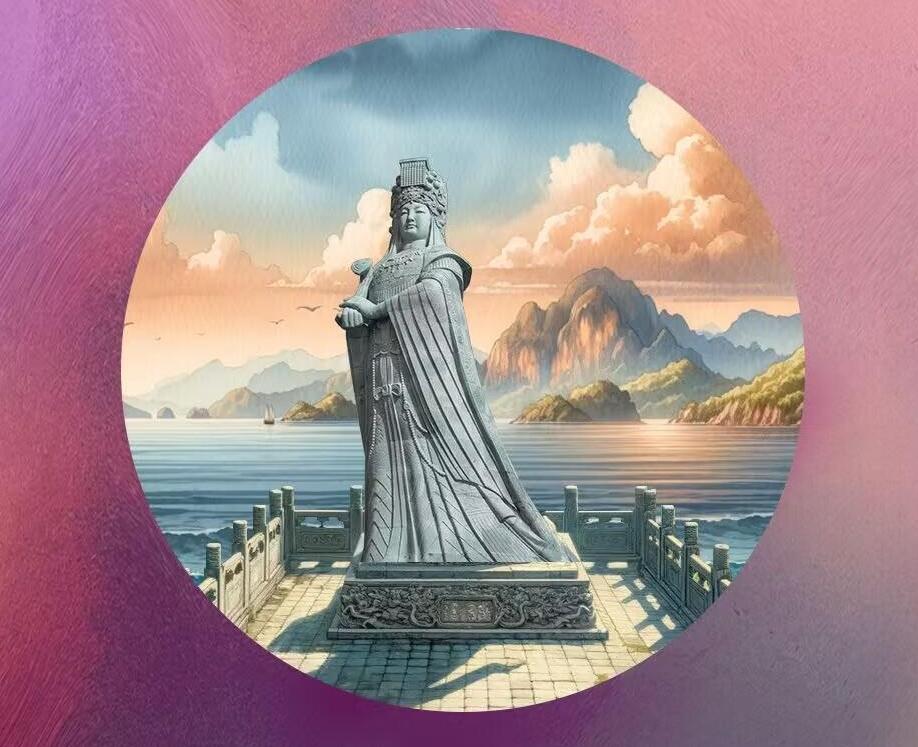

E-mail China.org.cn, May 24, 2024Editor's note: Mazu is the most influential sea goddess in China's coastal areas, boasting more than 200 million followers worldwide. In 2009, UNESCO included Mazu belief and customs on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

According to legends, in the year 960, a baby girl named Lin Moniang was born in a small fishing village on Meizhou Island in southeast China's Fujian province. Lin grew up to be clever, diligent and benevolent, helping many people with her kindness and expertise. However, she died young, at age 28, after rescuing her fellow fishermen in a shipwreck. After her death, locals erected a temple and began worshipping Lin as Mazu, the sea goddess.

Many other folktales about Lin's life are widely accepted, with varying details, but all are centered on the core values of love and devotion, as well as her personal charisma. Folklore experts believe the worship of Mazu also profoundly relates to the turbulence of the ancient times in which she lived.

The year 960 marked the start of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), ushering in stability after the chaotic and divisive Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-979). However, people in northern China still faced frequent conflicts with the Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. This led many to flee south to coastal areas, where they integrated with local culture and contributed to the development of Mazu beliefs and customs as they sought protection from the deity.

Since the Song Dynasty, Mazu's reputation gradually grew, with imperial courts expanding temples, building new statues, and bestowing official titles on the goddess. As a result, Mazu, which means "maternal ancestor" in Chinese, is also known by various other names and titles, such as the Queen of Heaven and the Holy Heavenly Mother.

Originally revered as a deity who protects the lives and voyages of fishermen and sailors, Mazu's believers now also pray to her for peace, pregnancy, or general well-being. Having been worshipped for over 1,000 years, Mazu currently has about 200 to 300 million followers in more than 20 countries and regions. Overseas Chinese communities often regard Mazu belief and customs as a cultural bond with their motherland.

Mazu's believers commonly hold worship ceremonies twice a year – one commemorating her birthday on the 23rd day of the third lunar month, and the other marking her death on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month. According to UNESCO, these ceremonies are held in more than 5,000 Mazu temples worldwide.

On Meizhou Island, Mazu's birthplace, these sacred events are significant to both locals and visitors. It is said that Mazu's believers, who live far away from Meizhou, treat their visits to Meizhou's temple as one of the most important events in their lives.

On the day of the ceremony, Meizhou's local residents and fishermen usually suspend their work and worship the deity's statue in the temple, following certain religious rituals and traditional customs. They present offerings to the deity, light candles, burn incense, display lanterns, and hold various performances.

Worship of Mazu can also take place within individual families. Family members usually place the statue of the deity on an altar table at home or on their boat. They also burn incense, make offerings, and pray for a safe voyage and a better life.

"Deeply integrated into the lives of coastal Chinese and their descendants, belief in and commemoration of Mazu is an important cultural bond that promotes family harmony, social concord, and the social identity of these communities," says UNESCO. In 2009, UNESCO added Mazu belief and customs to its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Discover more treasures from China on UNESCO's ICH list:

? 2022: Traditional tea processing

? 2020: Wangchuan ceremony, taijiquan

? 2018: Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa

? 2016: Twenty-four solar terms

? 2013: Abacus-based Zhusuan

? 2012: Training plan for Fujian puppetry performers

? 2011: Shadow puppetry, Yimakan storytelling

? 2010: Peking opera, acupuncture and moxibustion, wooden movable-type printing, watertight-bulkhead technology of Chinese junks, Meshrep

? 2009: Yueju opera, Xi'an wind and percussion ensemble, traditional handicrafts of making Xuan paper, traditional firing techniques of Longquan celadon, Tibetan opera, sericulture and silk craftsmanship, Regong arts, Nanyin, Khoomei, Mazu belief and customs